Summary:

-

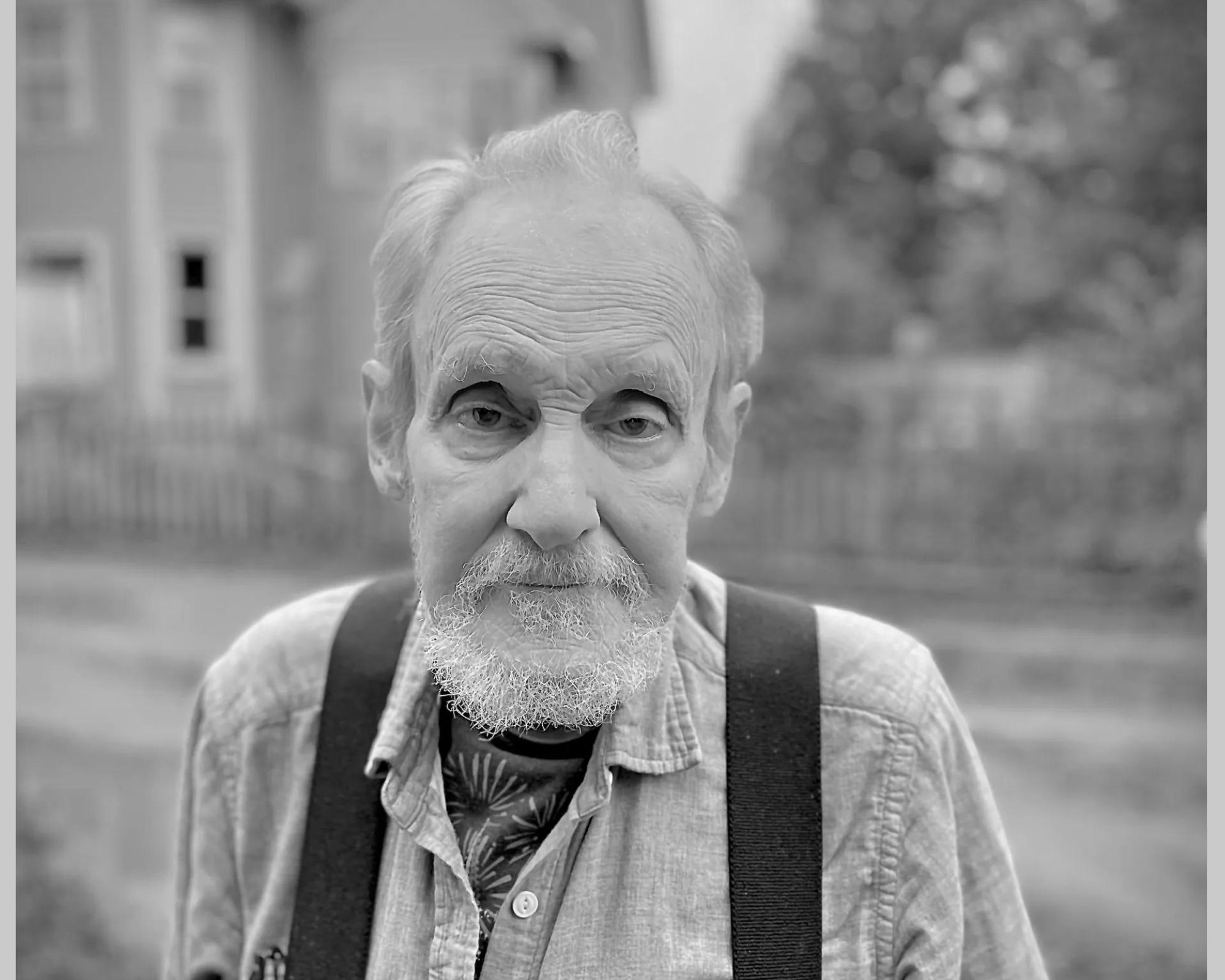

Peter Schjeldahl has been The New Yorker’s art critic for a long time.

-

He recently sent in a review of Hans Janssen’s new translation of Piet Mondrian’s biography.

-

Peter was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer in 2019.

-

They quickly became known for their Fourth of July parties, where Peter would set off so many fireworks that it looked like the end of the world and a patriotic celebration at the same time.

-

Ada asked Peter if he wanted to return to Rome or Paris after learning that he had cancer, an illness that he and his physicians managed to stave off for a more extended period than anyone could have predicted.

Sometimes a writer, an artist, or a person is so defiant of death that you start to believe what they say. Peter Schjeldahl has been The New Yorker’s art critic for a long time. He recently sent in a review of Hans Janssen’s new translation of Piet Mondrian’s biography. In Peter’s opinion, Mondrian and Picasso were the “twin pioneers of twentieth-century European pictorial art: Picasso the best painter who updated picture-making, and Mondrian the greatest modernizer who painted.” He is at his very best—his most intelligent, persistent, and personal—in this lengthy piece (longish for Peter, who is more of a sprinter than a miler):

Their level of criticism of him may fluctuate. However, there can be no ups or downs in Mondrian’s significance compared to other artists of the past, present, and future for anyone willing to pay it. There is only a constant state of meaning that can’t be put into one category and needs to be compared to other things. Even the critically acclaimed Janssen, with his magnum opus of biography, cannot solve the impenetrable riddle of the Dutch magus’s dead ends in lived time; he can only dance around it.

As we were about to press this Friday, word arrived that Peter had passed away. It’s hard to imagine what kind of strength he must have had in his last weeks to write in that way. Peter was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer in 2019. When he was sixteen, he first started smoking. He responded, “I’ve smoked a million cigarettes, and I’ve enjoyed every one,” when I asked him whether he was finally going to kick the habit. The joke became part of a routine, an act of cocky defiance, and then an extreme way of thinking. In his article “77 Sunset Me,” which came out soon after he was diagnosed, he wrote, “I know how to end a reliance.” I am an alcoholic who has been sober for 27 years. My life was ruined by alcohol. Tobacco only cuts it down to size, leaving off the most significant elements.

You would fail in your argument, even if you were willing to challenge its validity. Peter had strong ideas about a variety of topics, including art. After being lost for a long time, he was someone who had some survival skills. More than twenty years ago, we first met. I wanted to hire an art critic who would work full time. I had been reading him in the Village Voice for years. And he’s always had a voice, one that was distinct, clear, and humorous. A poet’s voice is concise and unfussy. On a Saturday in the late summer, we assembled at the workplace. The air conditioning in the building had been turned off. Peter had a pale complexion and was sweating heavily. I inquired about a blank space on his resume. Well, back then, I was a stumbling drunk. I then corrected that. Compared to artists, he was tougher on himself.

Don’t get me wrong; over the years he wrote for The New Yorker, Peter was perfectly willing to give a bad show a bad review, and there were some artists he would never like (Turner and Bacon among them). Still, he was also open-minded, knew how to praise critically, and, in the end, was open to new things and new artists. Velázquez, Goya, Rembrandt, Cindy Sherman, David Hammons, Martin Puryear, Rachel Harrison, and Laura Owens were a few of his many favourites. He was serious about his work—despite the torrents of self-criticism, I believe there were times when he realised how wonderful he was—but he never took himself too seriously. He once received funding for a memoir. He bought a tractor with the cash.

Peter was raised in a small, chilly Minnesota town. His parents had a little cash. Afterwards, they had fewer. He travelled to New York from New Jersey, like countless other young people, hoping to lead a different life—though he wasn’t sure what kind. He had to deal with problems, but when he met Brooke Alderson at the Whitney Museum, it was a huge stroke of luck. They relocated into a walkup on St. Mark’s Place in 1973. The dedication of their daughter Ada’s book “St. Marks Is Dead,” which she would go on to write, read: “To my parents, who looked at the apocalyptic East Village of the 1970s and thought, ‘What a lovely place to raise a baby’,”

The truth is that there’s no point in condensing everything into a light-hearted obituary style; instead, read “77 Sunset Me” to get an authentic feel of Peter’s thinking and his life. There, Peter will make jokes about his drinking, his love of life, and the challenges of writing well. After hearing the bad news from his doctors, you’ll understand why he’s so happy about small wins: “swatted a fly the other day and thought,” outlived you.”

In the ’80s, Peter and Brooke purchased a home in the village of Bovina, three hours north of the city. They quickly became known for their Fourth of July parties, where Peter would set off so many fireworks that it looked like the end of the world and a patriotic celebration at the same time. Hundreds were present, both those who were invited and others who weren’t. It was a big, dangerous potluck lunch with a lot of pies, hot dogs, and things that could go wrong. The most recent event was in 2015, and about 2,000 people went because of social media. Peter didn’t break any laws. He told Times writer Ginia Bellafante, “We were lawful till the end.” The police and fire departments brought families. This nation is libertarian.

Ada asked Peter if he wanted to return to Rome or Paris after learning that he had cancer, an illness that he and his physicians managed to stave off for a more extended period than anyone could have predicted. “No,” he replied. Perhaps a baseball game, the Mets vs. Braves game, was scheduled by Ada, according to Peter, “with family and friends, at Citi Field.” Glorious. Oliver, the grandson, successfully caught a T-shirt fired mid-game. The likelihood of such a thing is thousands to one.

Analysis by: Advocacy Unified Network