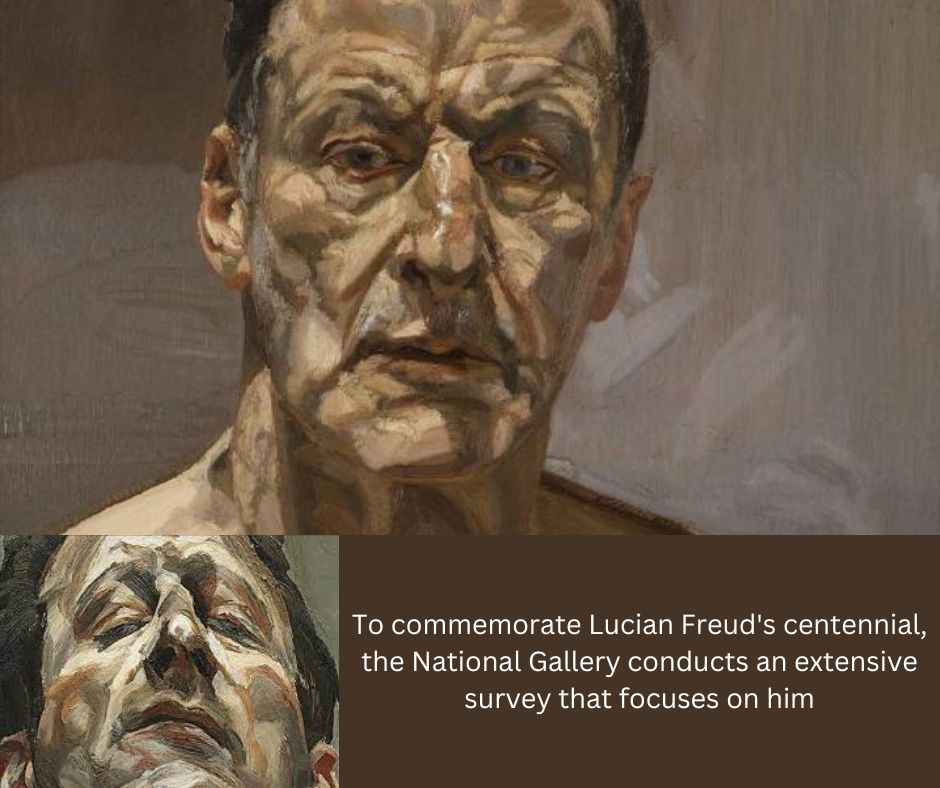

Summary: Lucian Freud (1922–2011) is being held in conjunction with the artist’s 100th birthday. Daniel Herrmann: “The time is right to give Freud another look”. Younger painters are currently drawn to his work, he claims. According to Freud, “Life is art, the flesh is paint, and paint is flesh”. Sigmund Freud’s Anatomical Paintings In The National Gallery, London, are to be shown for the first time in the UK.

Curator Hermann Herrmann wants to emphasise Freud’s close relationship with the gallery and his dedication to flesh and nakedness. Freud’s portraits of Leigh Bowery and Sue Tilley have undergone a paradigm shift in how they are perceived. Herrmann wants to emphasise Freud’s close relationship with the National Gallery. Large Interior W11 (after Watteau) (1981–1983) is the most well-known example.

How much is excessive? The National Gallery is asking this question as it opens the highly anticipated Lucian Freud (1922–2011) exhibition, which is being held in conjunction with the artist’s 100th birthday. There have been around a dozen exhibitions of Freud’s work in London alone over the past 20 years, including significant surveys at the National Portrait Gallery in 2012 and the Royal Academy of Arts in 2019. Freud is undoubtedly everywhere. While other smaller shows will run concurrently with the National Gallery’s, Freud was on display at Tate Liverpool last year.

Daniel F. Herrmann, the curator of Lucian Freud: New Perspectives at the National Gallery, asserts that the institution has the power to change the situation. People like to view his work, and there is much to consider. Therefore his popularity speaks to the calibre of his career. However, I also believe that many displays present preexisting perspectives on Freud. The time is right to give Freud another look. That’s what we’re attempting to accomplish, and we’re lucky that we can use it as an institution.

In essence, Herrmann’s strategy involves repositioning a significant figure. Younger painters are currently drawn to his work, he claims. “Figuration, what it does, how it delivers messages, and what it can do, are all experiencing a tremendous rebirth. The answers to all of these queries relate to Freud.

What, then, is this novel idea? Herrmann says he respects “how radical Freud is about the art of painting” and how “dedicated” he is to it. “The task needs and rewards radical gazing,” he continues. You learn a lot when you attempt to understand how each painting functions. A significant component of it is Freud’s dedication to flesh and nakedness. “The subject is truth. Not just through photorealism or raw authenticity, but through honesty—what is a person’s genuine nature? According to Freud, “Life is art, the flesh is paint, and paint is flesh.”

Herrmann has engaged Tracey Emin, Jutta Koether, and Chantal Joffe to contribute to the catalogue; all talk of the frankness and closeness Freud attained, supporting his claim that figuration has new relevance. According to Herrmann, the portraits of Leigh Bowery and Sue Tilley (the “benefits supervisor”), which are among Freud’s most striking works, have undergone a paradigm shift in how they are perceived. “Freud was frequently referred to be a painter with an “unflinching eye” or a “cruel look” ten or twenty years ago. However, the things that individuals perceived as harsh sprang from their own opinions on the matter. Freud, who openly celebrates them, will depict a figure with a non-normative body. This is why figuration is so popular today: it provides us with a method to think about our identities as individuals.

Sigmund Freud’s Anatomical Paintings In The National Gallery

Herrmann wants to emphasise Freud’s close relationship with the National Gallery, where he was occasionally permitted to wander after hours. This is where the artist discovered a passion for using famous works of art to inspire his creations. The most well-known example is Large Interior W11 (after Watteau) (1981–1983), which was influenced by the French painter of the same name. Herrmann also draws attention to Freud’s 1993 naked self-portrait, Painter Working, Reflection, which the curator claims relates to Michelangelo’s self-portrait as St. Bartholomew, depicted holding his own flayed skin, and Vincent van Gogh’s painting of his boots.

Is this display Freud’s final work? Hermann hopes not. He claims that Freud is among the best figurative artists in the world and merits a fresh perspective. “I hope it will enable a lot of new exhibitions, new questions, and new ideas in the future when people get the chance to reassess what Freud is,” the author said.

What, then, is this novel idea? Herrmann says he respects “how radical Freud is about the art of painting” and how “dedicated” he is to it. “The task needs and rewards radical gazing,” he continues. You learn a lot when you attempt to understand how each painting functions. A significant component of it is Freud’s dedication to flesh and nakedness. “The subject is truth. Not just through photorealism or raw authenticity, but through honesty—what is a person’s genuine nature? According to Freud, “Life is art, the flesh is paint, and paint is flesh.”

Herrmann has engaged Tracey Emin, Jutta Koether, and Chantal Joffe to contribute to the catalogue; all talk of the frankness and closeness Freud attained, supporting his claim that figuration has new relevance. According to Herrmann, the portraits of Leigh Bowery and Sue Tilley (the “benefits supervisor”), which are among Freud’s most striking works, have undergone a paradigm shift in how they are perceived. “Freud was frequently referred to be a painter with an “unflinching eye” or a “cruel look” ten or twenty years ago. However, the things that individuals perceived as harsh sprang from their own opinions on the matter. Freud, who openly celebrates them, will depict a figure with a non-normative body. This is why figuration is so popular today: it provides us with a method to think about our identities as individuals.

Herrmann wants to emphasise Freud’s close relationship with the National Gallery, where he was occasionally permitted to wander after hours. This is where the artist discovered a passion for using famous works of art to inspire his creations. The most well-known example is Large Interior W11 (after Watteau) (1981–1983), which was influenced by the French painter of the same name. Herrmann also draws attention to Freud’s 1993 naked self-portrait, Painter Working, Reflection, which the curator claims relates to Michelangelo’s self-portrait as St. Bartholomew, depicted holding his own flayed skin, and Vincent van Gogh’s painting of his boots.

Is this display Freud’s final work? Hermann hopes not. He claims that Freud is among the best figurative artists in the world and merits a fresh perspective. “I hope it will enable a lot of new exhibitions, new questions, and new ideas in the future when people get the chance to reassess what Freud is,” the author said.

Analysis by: Advocacy Unified Network