Summary:

-

We asked a variety of creators and critics to respond to our survey, which found that just 11 percent of acquisitions at 30 U.S. museums were of work by female-identifying artists, and only 2.2 percent were by Black American artists between 2008 and 2020. Here’s what they said.

-

Change in the demographics of who is acquired by museums or sold at auction is happening, and I believe it is trending positively.

-

The close correspondence between the rates at which U.S. museums are acquiring works by Black and female-identified artists and rates of auction sales indicates the continued influence of the art market on U.S. museums.

-

This is why it is essential for public and non-profit museums to free themselves from its influence.

-

Looking at this information without looking at who controls and makes choices in the system is critical to a holistic approach to fully addressing coordinated exclusion.

When we presented people with the findings of our latest survey on representation in the art world, most were shocked. But artists were less surprised than most; many live this reality daily. We asked a variety of creators and critics to respond to our survey, which found that just 11 percent of acquisitions at 30 U.S. museums were of work by female-identifying artists, and only 2.2 percent were by Black American artists between 2008 and 2020.

Here’s what they said.

Deborah Kass

“There were no surprises for me reading through the thorough and infuriating Burns Halperin Report; I doubt any female artist who has been aware of the art market in any way.

When asked to respond, I had way too much to say about minority rule and white male supremacy and their manifestations in inequities in the art market and museum acquisitions. So I remembered this piece from 2010 [above].

The exact Louise Bourgeois quote I elaborated on is: “A woman has no place as an artist unless she proves over and over again she won’t be eliminated.” I thought this could be interpreted as unfair to women artists. So I sharpened the quote to bring LB, a woman of her time, into ours.

I did this because the problem is not women. It is the world we live in.

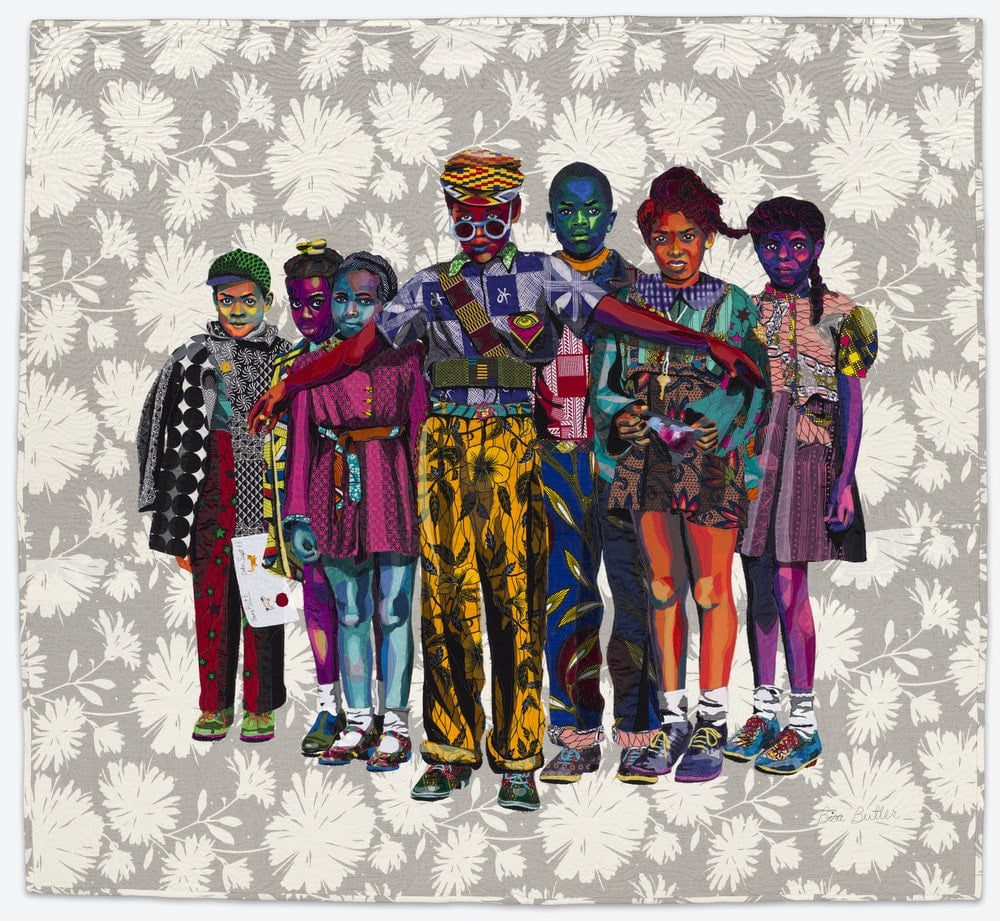

Bisa Butler

Bisa Butler, The Safety Patrol (2018), was purchased by the Art Institute of Chicago from Claire Oliver Gallery at PULSE Miami Beach 2018. Photo courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago, Cavigga Family Trust Fund.

“I could say these numbers are discouraging, but that isn’t entirely true. While it is abysmal, I tend to be optimistic and believe that while these numbers represent the major museums, there is an underground art market where Black people buy art from Black galleries and institutions. They may not have been included in the study sample. Yet still, I am aware that this study is a reliable tool to expose whitewashing in American art.

Unfortunately, black women have been traditionally shut out of gaining financial wealth in the United States, and the art market is no different. Fortunately, I grew up with parents who taught me about strong women who succeeded despite hardships that were exponentially greater than mine. I grew up reading about Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Shirley Chisholm, and Madam C.J. Walker.

I know these women do not represent most black women negatively affected by our racially imbalanced financial system. Still, I am mindful that determination, mass actions, and demonstrations can enact change. Today’s artists, writers, and thinkers can face this discrimination in art and actively work to change it if they choose to.

We cannot pretend discrimination and racism don’t exist; we must face them.

“Studies like the Burns Halperin Report speak truth to power and pave the way for change, and I hope I can be a part of the long line of women activists who fought for justice and all forms of equality.”

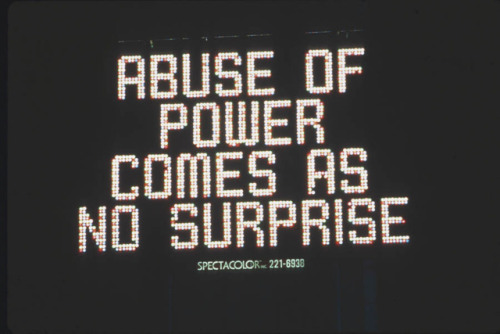

Jenny Holzer

Jenny Holzer, Untitled (1982). Photo by John Michael.

“Recognize—and pay—all the women of many colours who have the magic. “CELEBRATE THE WOMEN WHO HAVE MADE IT despite and because of their gender.”

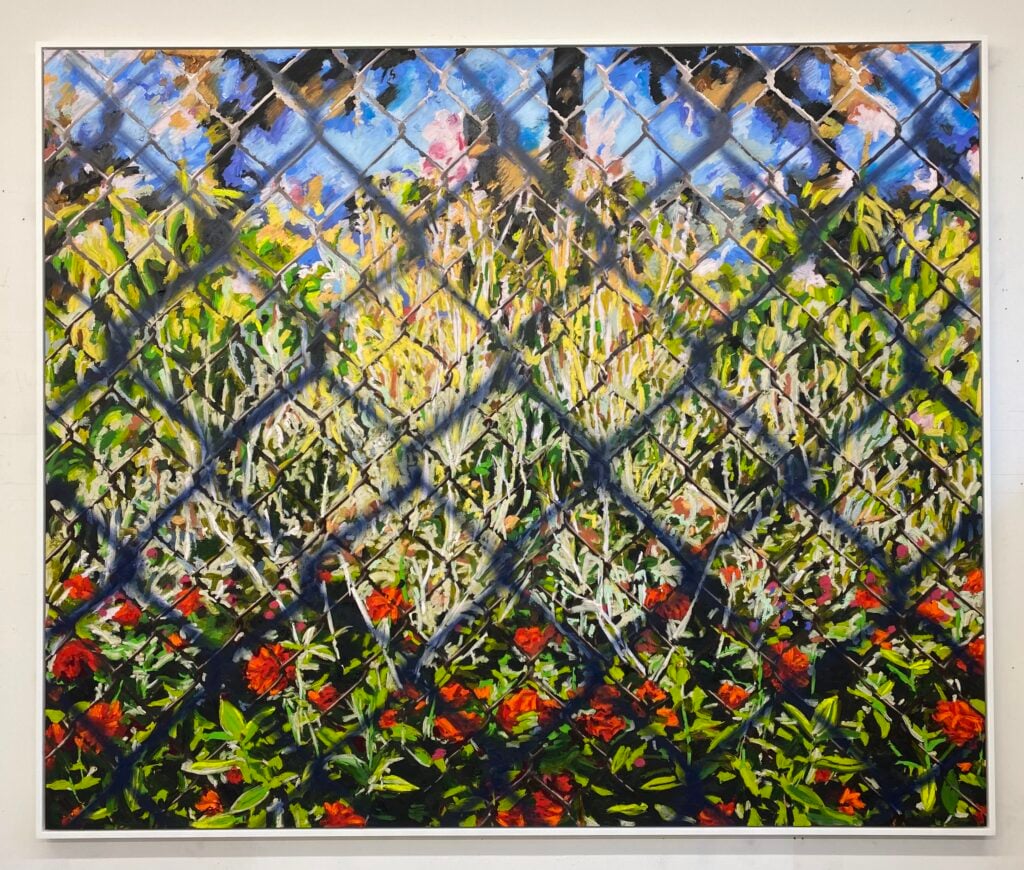

Paul Anthony Smith

Paul Anthony Smith, Dreams Deferred #53 (2022). Courtesy of the Artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

“There is so much to be said. The collected data is important and objectively measures what is seen and felt. Change in the demographics of who is acquired by museums or sold at auction is happening, and I believe it is trending positively. The complexion of the art market is often dictated by who is collecting what, and it trickles down to which artists get major representation. Time and time again, we see museums that organize exhibitions based on popularity. Still, it does not always align with the interests of the community within them in highlighting diverse voices. Auction inclusions are also often dictated by who’s making the next big leap to a blue-chip gallery or who will have the next great museum show. “It’s a system I’ve watched for almost 15 years, and I’m never surprised by the annual results, but I think change takes time.”

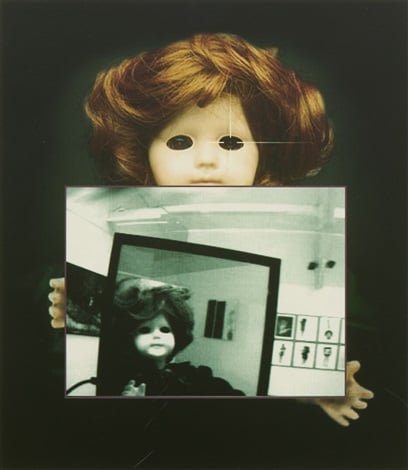

Laurie Simmons

Laurie Simmons, from the series “How We See (Look 1: Daria)” (2014). Courtesy of the artist

“I find these numbers useful because there’s something tangible to refer to.” I’m often asked if the art world is a better place for women artists now than when I started in the late ’70s. I got used to being the buzzkill and answering who answered, ‘no, not really.’

Lately, I hear it as more of a declarative sentence, as in, ‘The current art world is a better place for women artists and Black and brown artists and LGBTQ artists etc than it ever has been.’

I get it. It’s comforting for people to think there has been progressing, but the numbers tell a different story, or at least one less hopeful story. What is true is that there’s much wing-flapping and a kind of institutional hysteria around catching up, particularly around moments of cultural upheaval like BLM and the uprising around the murder of George Floyd. However, institutions competing to shift representational demographics is not the same as a genuine reorganization of access, resources, and power. This particular soufflé rises and sadly collapses as soon as it gets out of the oven. It seems that after these attempts to get a handle on things, people tend to forget the critical changes that have happened.

What I find different about this particular moment is the questioning of institutions, histories, hierarchies, and gatekeepers in a way I don’t recall happening when I was starting, at least in my particular bubble of the art world. We (or some of us) had the impression that the fundamental structures of institutions and industry were sound. We believed that the basic statistics—representation, price points, etc.—needed to change to make things right. That was not true. The systemic dysfunction of the structures wasn’t called out to the degree, and with the magnitude, they are today, and that’s a good thing.”

Robert Clarke-Davis

“It’s art; who cares. I’m more worried about the lack of diversity in medicine, not among those who see themselves as overly self-important.”

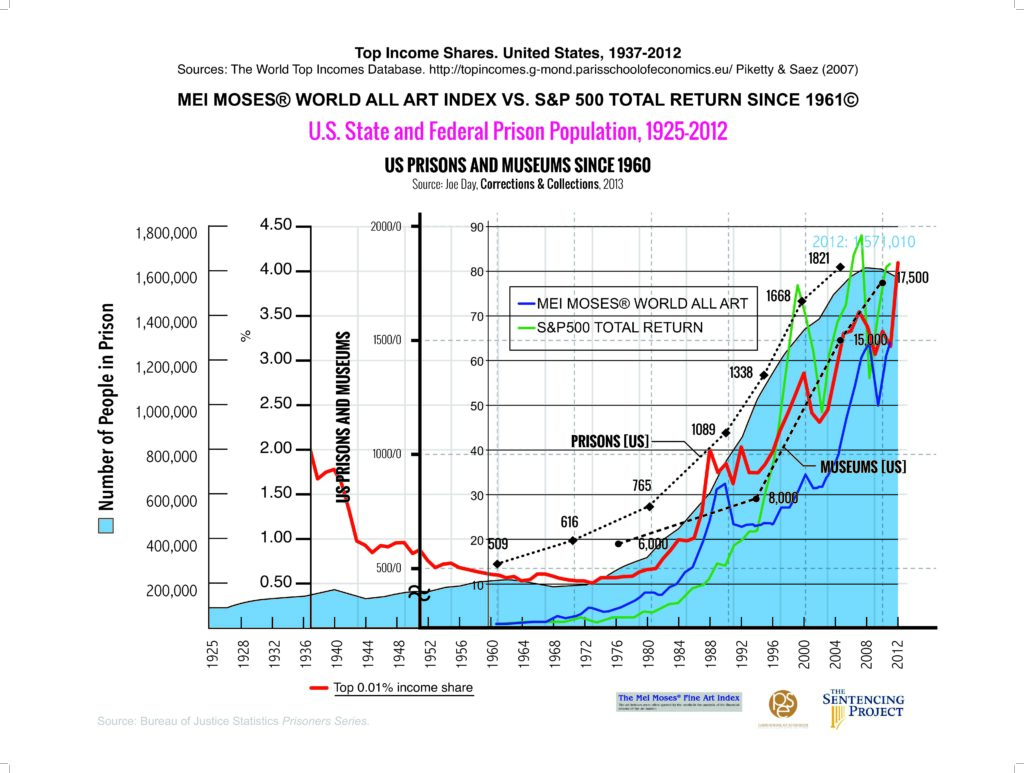

Andrea Fraser

Andrea Fraser, Index II (2014), graph. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery

“I commend Burns and Halperin for their urgently necessary research, which demonstrates the dismal lack of progress toward equity for Black and female-identified artists in the art market and U.S. art institutions. Particularly surprising for me is the extreme inequity that persists in exhibitions. The numbers cut through my sense of progress toward equity in exhibitions and programs in the institutions I follow, exposing a gap in perception that only research like theirs can reveal.

It is heartening, at least, to read that the rates for acquisitions by contemporary art museums are closer to reflecting U.S. demographics than the terrible numbers for U.S. museums as a whole. That art museums are exhibiting Black artists at almost three times the rate of acquisitions (6.3 percent versus 2.2 percent) reveals the superficiality and duplicity of institutional representation and the urgent need for structural change, not just the diversification of programs.

The close correspondence between the rates at which U.S. museums are acquiring works by Black and female-identified artists and rates of auction sales indicates the continued influence of the art market on U.S. museums. I have a hard time considering the art market, an economic sector built on inequity, as a benchmark for equity of any kind. Even the Art Basel UBS Global Art Market Report now tracks increasing wealth concentration as an indicator of positive art market prospects. As an extreme example of a plutonomy within extractive patriarchal, colonial, and racial capitalism, any progress toward equity in the art market could never be more than superficial without significant structural economic change.

This is why it is essential for public and non-profit museums to free themselves from its influence.”

Ghada Amer

Installation view, “Ghada Amer—A Retrospective: A Woman’s Voice is Revolution.” Photo © Jean-Christophe Lett at the Vieille Charité, Marseilles

“I have always believed the battle is in the economy and the sale price. There is SOOOO MUCH STILL to do.

Many museums do not buy me, and my auction prices are horribly, and my fees are SUPER LOW compared to my peer artists.

It is depressing and frustrating.”

Lynn Hershman Leeson

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Tillie and Mirror (1998). Courtesy of G. Austin Conkey Collection.

“I think change will not happen until institutions, collectors, and grantmakers are held accountable. There need to be coordinated actions that will, on a substantial agenda, not only call attention to the discrimination but limit access to the museums or galleries that are not equitable until they shift their policies and mentality. Perhaps have all galleries and museums even list percentages at the entrance?”

Paul Rucker

Paul Rucker, Banking While Black being installed in Tempe, Arizona. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News.

“If you frequent museums, you know there’s a history of coordinated exclusion—none of this is an accident. We can’t talk about fixing a system that’s working exactly as designed.

Controlling the narrative by controlling whose creativity, voice and presence are valued, whose objects are put on display, and whose ideas are published has always been a key to those in power to maintain the status quo.

The Burns Halperin Report is incomplete. Looking at this information without looking at who controls and makes choices in the system is critical to a holistic approach to fully addressing coordinated exclusion. Where’s the data showing the gender, racial, and socioeconomic breakdown of the people who work in the administrative offices and are the decision-makers? The directors, administrators, staff, collectors, curators, and boards of museums, art markets, galleries, and auction houses? We mustn’t allow these institutions to include janitorial and security staff to inflate their diversity numbers. The other critical roles in this ecosystem must also be analyzed. This is the only way we can see the correlations if we intend to address the current system.

We are in a dangerous place right now with performative actions that give the illusion of progress. Whenever an issue is inadequately addressed, the unresolved issue gets more robust and more resilient, and in most cases, the harm gains momentum. This is where we are right now.”

Clarice Lispector

слава україні!!

“O que obviamente não presta sempre me interessou muito. Gosto de um modo carinhoso do inacabado, do malfeito, daquilo que desajeitadamente tenta um pequeno vôo e cai sem graça no chão.”

“What sucks has always interested me a lot. I love affectionately the unfinished, the poorly done, what clumsily tries a short flight and falls awkwardly to the ground.”

Jerry Saltz

“Once a year, for about 20 years, I used to go to MoMA to count the number of works made by women-identifying artists on exhibit in the vaunted permanent collection before 1970. Then I wrote about what I saw—or, as was the case, didn’t see.

When MoMA reopened its horrendous 2004 building, after spending three-quarters of a billion dollars, it failed to add more space for the permanent collection and then had to be essentially then rebuilt again to fix Glenn Lowry’s sad mistake—just 3 percent of the works on display on this shiny new building were by women.

How could that have happened? It did after the art world made all its noise about how progressive and open it was. I recall that Georgia O’Keeffe was either not on view or was by the escalators and bathrooms. Over the next seven or eight years, the numbers went up. But not by much. I understand one part of this. You can’t go back and change the percentage of the modernists who were women or who MoMA collected.

All collecting institutions work within very set perimeters. As an Estonian immigrant, I can’t expect Whitney to collect more great Estonian first-generation Abstract Expressionists because there probably weren’t many. But this kind of history can be corrected in places. But not by taking enormous polls of multiple institutions that serve different purposes, periods, locations, mediums, and much more. I view all the numbers in extensive polls of what museums collect, buy, and exhibit, not that telling. You can quickly cook the books to make these things tell you anything you want.

Rather than polls, I pay close attention to museum wall labels and their accession numbers. My wife, Roberta Smith, taught me that’s where the real story of a museum is told. She’s right. This number tells you exactly when the work was acquired. If the number is 2019.10.3, it might mean the work was bought in 2019, in October and was the third work purchased that month. You can see how and when, and how much art is entering a collection and by whom. It’s thrilling, really, this peak behind the museum curtains.

Pay attention these days, and you’ll instantly see how many works are by women or underrepresented artists. Judging these, you see how hard—or not hard, in some cases—museums are trying to the right decades or more of wrong.

We haven’t reached anything like co-equality. It took decades to make some institutions so unrepresentative. For a time, the roadmap of Modernism was almost all in French: Take Géricault, past Delacroix, ’til you get to Corot, turn left at Courbet until you get to Manet; then go straight through Degas, Monet, Renoir till you get to Seurat and Van Gogh. Make a right until you get to Cezanne. It’s laughable in retrospect that anyone would fashion art in linear and nationalistic terms. But white men will be white men.

The art was great; the ideology was idiotic.

It’s going to take some time to put this world in some balance.

When it comes to art by women-identifying artists, I’m thrilled that I’m finally seeing getting to see more than half the story that was missing.”

Analysis by: Advocacy Unified Network