Summary:

- Even though he was at the pinnacle of his career, he continued to be subjected to racist treatment, which he found to be an even greater source of annoyance.

- Mr. Belafonte was criticized as a pretender.

- Despite the fact that both Dorothy Dandridge and Mr. Belafonte were outstanding vocalists, their singing voices in “Carmen Jones” were dubbed by opera singers.

- During the course of the campaign, he referred to the wealthy industrialist brothers Koch as “white supremacists” and linked them to the Ku Klux Klan.

- In his later years, he was awarded a number of prestigious honors, including a Kennedy Centre Honour in 1989, the National Medal of Arts in 1994, and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000.

- In the same year that his autobiography, titled “My Song,” was released, he was also the subject of the documentary film “Sing Your Song.

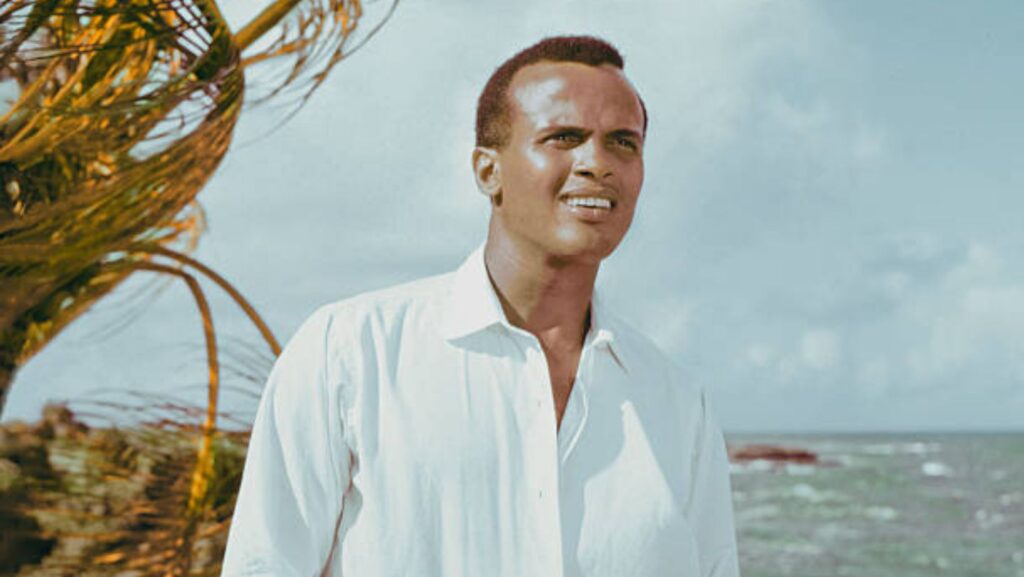

Harry Belafonte, a boundary-pushing singer, actor, and activist, passed away at the age of 96.

His rise to prominence in the entertainment industry in the 1950s, a time when racial discrimination was still pervasive throughout most of the country, was a landmark achievement. However, he prioritized issues pertaining to civil rights.

Harry Belafonte passed away on Tuesday at his home on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. During the 1950s, he dominated the pop charts and broke down racial barriers with his very personal brand of folk music. He went on to become a driving figure in the battle for civil rights. Belafonte’s death comes as a great loss to the world. He was 96.

According to Ken Sunshine, who has been his publicist for many years, the cause of death was congestive heart failure.

A landmark achievement in adverse situations

Mr. Belafonte’s rise to the pinnacle of the entertainment industry at a time when racial discrimination was still pervasive and black actors were still a rarity on both large and small screens, was a landmark achievement. He was hardly the first Black entertainer to break down racial barriers; Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, and others had already gained popularity before he did. However, no one had made as large of a mark as he did, and for a few years after that, no one in music, black or white, was bigger than he was.

He almost single-handedly started a craze for Caribbean music with hit records such as “Day-O (The Banana Boat Song)” and “Jamaica Farewell.” His album “Calypso,” which included both of those songs, reached the top of the Billboard album chart shortly after its release in 1956 and remained there for 31 weeks. He was born in Harlem to West Indian immigrants. It was reported to have been the first record by a single artist to sell more than a million copies, and it came out soon before Elvis Presley became successful in his career.

The most highly-paid Black performer

Mr. Belafonte was equally successful as a concert attraction. Handsome and charismatic, he held audiences spellbound with dramatic interpretations of a repertoire that encompassed folk traditions from all over the world, including rollicking calypsos like “Matilda,” work songs like “Lead Man Holler,” and tender ballads like “Scarlet Ribbons.” By 1959, he was the most highly-paid Black performer in history, with fat contracts for appearances

Mr. Belafonte was the first African American actor to gain considerable success in Hollywood as a leading man shortly after he began receiving movie offers as a result of his popularity as a singer. His success in the movies was fleeting, however, and it was Mr. Belafonte’s friendly rival Sidney Poitier, not Mr. Belafonte, who went on to become the first legitimate Black matinee idol.

However, Mr. Belafonte never placed a high priority on his career in the film industry, and after a while, neither did his musical career. Although he continued to perform into the 21st century and also appeared in films (although he took two long breaks from the big screen), his primary concern from the late 1950s onward was civil rights. He had two long breaks from the big screen.

During the early stages of his professional life, he developed a friendship with the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He went on to become not just a friend for the rest of his life but also an ardent supporter of Dr. King and the fight for racial equality that he symbolized. He was one of the major fund-raisers for both the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and he contributed a significant portion of the seed money that was needed to get the organization off the ground.

Protecting the King family

He contributed financially so that Martin Luther King, Jr., and other civil rights advocates might be released from jail. In 1963, he was one of the participants in the March on Washington. Dr. King made the comfortable flat on Manhattan’s West End Avenue, which was quite large, his home away from home. In addition, he privately kept an insurance policy on Dr. King’s life, naming the King family as the beneficiary of the policy. He gave his personal money to ensure that the family was cared for after Dr. King was killed in 1968. Both of these actions ensured that the family was taken care of.

(Nevertheless, in 2013, he filed a lawsuit against Dr. King’s three surviving children in a disagreement over records that Mr. Harry Belafonte claimed were his property and that the children maintained belonged to the King’s estate. The litigation was settled the following year, with Mr. Belafonte keeping control of the documents.)

Mr. Belafonte discussed his conflicted feelings over his prominent role in the civil rights struggle in an interview with The Washington Post that took place a few months after the passing of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. He stated that he would like to “be able to stop answering questions as though I were a spokesman for my people.” He went on to say, “I hate marching and getting called at 3 a.m. when I don’t want to get up.” to get several felines out of jail, but he added that he understood his responsibility and accepted it.

The Problem That Racism Presents

Although he sang music that had “roots in the Black culture of American Negroes, Africa and the West Indies,” the majority of his admirers were white even though he sang music that had “roots in the Black culture of American Negroes, Africa and the West Indies,” according to the same interview. Even though he was at the pinnacle of his career, he continued to be subjected to racist treatment, which he found to be an even greater source of annoyance.

His role in the 1957 film “Island in the Sun,” which contained the suggestion of a romance between his character and a white woman played by Joan Fontaine, generated outrage in the South. In fact, a bill was even introduced in the South Carolina Legislature that would have fined any theatre that showed the film. In 1962, while Mr. Belafonte was in Atlanta performing at a charity concert for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he twice turned away from the same restaurant because of his race. Television appearances with white female singers, such as Petula Clark in 1968 and Julie Andrews in 1969, infuriated a large number of viewers and, in the case of Ms. Clark, put him in danger of losing a sponsor.

Black wife to a white wife

It was suggested early on in his career that he attributed his success to the lightness of his complexion (his maternal grandmother and paternal grandpa were both white), which was one of the instances in which he was subjected to criticism from persons of African descent. When he divorced his wife in 1957 and married Julie Robinson, who had been the only white member of Katherine Dunham’s dancing group, The Amsterdam News reported, “Many African Americans are wondering why a man who has waved the flag of justice for his race should turn from a black wife to a white wife.” This was in response to the fact that he had married Julie Robinson.

King of Calypso

When Mr. Harry Belafonte’s record company, RCA Victor, advertised him as the “King of Calypso,” Trinidad, the acknowledged origin of that highly rhythmic song, attacked him as a pretender. In Trinidad, an annual competition is held to designate a calypso king. Mr. Harry Belafonte was criticized as a pretender.

When it came to calypso or any of the other traditional genres he admired, he never claimed to be a traditionalist, much less the monarch of calypso. He also never called himself a purist. He added that he and the other songwriters with whom he collaborated appreciated folk music but that they didn’t think there was anything wrong with putting their own spin on it.

Purism is the best cover-up for mediocrity

In 1959, he stated in an interview with The New York Times that “Purism is the best cover-up for mediocrity.” “If there isn’t going to be any change, we might as well go back to the very first ugh, which I assume was the very first song,” he said.

On March 1, 1927, Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. made his debut in the world in Harlem. His mother, Melvine (Love) Bellanfanti, who was born in Jamaica, worked as a domestic worker. Father of Belafonte, who was born in Martinique but later changed the family name, worked as a chef on merchant ships and was gone a lot of the time. His father eventually changed the family name.

In 1936, Harry, his mother, and his younger brother Dennis relocated to Jamaica. Harry was 11 years old at the time. Because she was unable to find work there, his mother quickly moved back to New York, leaving him and his brother in the care of relatives who, as he later recalled, were either “unemployed or above the law.” They eventually caught up with her in Harlem in the year 1940.

Awakening to the Importance of Black History

In 1944, Mr. Belafonte did not graduate from George Washington High School in Upper Manhattan. Instead, he enlisted in the Navy and was given the duty of loading explosives onto ships. He served in the Navy until 1946. His black shipmates encouraged him to learn more about the history of black people and introduced him to the writings of W.E.B. Du Bois and other African American authors.

When he was stationed in Virginia, he met Marguerite Byrd, the daughter of a Washington family from the middle class. She attended the Hampton Institute, which is now known as Hampton University, to obtain her degree in psychology. She provided him with more support and encouragement. They tied the knot in 1948.

Family

He is survived by his two children, Ms. Byrd, Adrienne Biesemeyer, and Shari Belafonte, as well as his two children with Ms. Robinson, Gina Belafonte and David, as well as eight grandchildren. In 2004, he and Ms. Robinson got a divorce, and in 2008, he married Pamela Frank, who is a photographer. Pamela Frank is one of the people who survive him, along with his stepdaughter Sarah Frank, stepson Lindsey Frank, and three step-grandchildren. Ms. Robinson was one of the people who survived him.

When Mr. Belafonte was back in New York after being discharged, he developed an interest in acting and signed up for the G.I. Acting Programme. Marlon Brando and Tony Curtis were among Bill’s classmates at Erwin Piscator’s Dramatic Workshop. Bill attended this workshop. It was at the American Negro Theatre in Manhattan, where he worked as a stagehand and where he met Sidney Poitier, a fellow theatrical rookie, that he made his debut on stage for the first time. This bond would last him the rest of his life.

It was difficult for Mr. Belafonte to find roles that were anything other than what he referred to as “Uncle Tom” characters. Despite the fact that singing was not much more than a hobby for him, Mr. Belafonte found an audience as a singer rather than as an actor.

At the beginning of 1949, he was offered the opportunity to perform at the Royal Roost, a well-known jazz nightclub located in Midtown Manhattan, during intermissions for a period of two weeks. He was an instant success, and the two weeks turned into five months very quickly.

Finding Folk Music

Mr. Harry Belafonte sought new sources of creativity after finding that his career as a jazz-influenced pop singer brought him some recognition but nothing in the way of artistic fulfillment. Together with the guitarist Millard Thomas, who would become his accompanist, and the writer and novelist William Attaway, who would collaborate on many of his songs, he immersed himself in the study of folk music. Millard Thomas would later become his accompanist. William Attaway would cooperate on many of his songs. (The calypso singer and songwriter Irving Burgie was later responsible for providing a significant portion of his repertoire, including the songs “Day-O” and “Jamaica Farewell.”)

Acting

His manager, Jack Rollins, assisted him in developing an act that highlighted his acting ability and his striking good looks as much as a voice that was husky and expressive but, as Mr. Belafonte confessed, was not very powerful. His manager helped him construct an act that emphasized his acting ability and his striking good looks as much as his voice.

After a successful engagement in 1951 at the Village Vanguard in Greenwich Village, the performer went on to have even greater success at the Blue Angel, the posh sister room of the Village Vanguard, which was located on the Upper East Side. Because of this, he was offered a recording contract with RCA and cast in the 1953 Broadway revue “John Murray Anderson’s Almanack.”

The big break

With a repertoire that included the calypso anthem “Hold ’em Joe” and his arrangement of the folk song “Mark Twain,” Mr. Belafonte garnered positive reviews, television bookings, and a Tony Award for outstanding featured actor in a Musical. Otto Preminger, a Hollywood producer, and director, noticed him as well and put him in the film version of “Carmen Jones” in 1954. Carmen Jones was an all-Black remake of Bizet’s opera “Carmen,” with lyrics written by Oscar Hammerstein II. Carmen had been a hit on Broadway a decade earlier.

Dorothy Dandridge, with whom Mr. Harry Belafonte had previously performed the year before in his first movie, the little-seen low-budget drama “Bright Road,” was Mr. Belafonte’s co-star in “Carmen Jones.” Despite the fact that both Dorothy Dandridge and Mr. Belafonte were outstanding vocalists, their singing voices in “Carmen Jones” were dubbed by opera singers.

Mr. Belafonte also made headlines for a movie that he turned down, citing what he deemed the picture’s ugly racial stereotypes. That movie was the cinematic adaptation of “Porgy and Bess,” which was released in 1959 and was also a Preminger production. Instead, his longtime buddy Mr. Poitier was offered the part of Porgy, and he harshly criticized Mr. Poitier for accepting the role in public.

Taking a Break From the Movies

During the 1960s, while Mr. Poitier was becoming a great box-office attraction, Mr. Harry Belafonte did not make any films at all. He claimed that Hollywood was not interested in the socially aware films he wanted to create, and he was not interested in the roles that were offered to him. On the other hand, he established himself as a regular face on television, where he was also known to stir up some debate on occasion.

His special “Tonight With Belafonte” won an Emmy in 1960, which was a first for a Black performer. However, a deal to do five more specials for that show’s sponsor, the cosmetics company Revlon, fell through after one more was broadcast. According to Mr. Belafonte, Revlon asked him not to feature Black and white performers together on the same show. Petula Clark’s appearance on a program that was being taped in 1968 was cut short when she accidentally touched Harry Belafonte on the arm. A representative from the show’s sponsor, Chrysler-Plymouth, ordered that the segment be redone. (The producer declined, and a representative of the sponsor apologized afterward, but Mr. Belafonte stated that the apology was “one hundred years too late.”)

Returning to the film industry

When Mr. Harry Belafonte returned to the film industry in 1970 with “The Angel Levine,” based on a story by Bernard Malamud, he did so as both a producer and a co-star alongside Zero Mostel. The project had a sociopolitical edge: His Harry Belafonte Enterprises, with the help of a grant from the Ford Foundation, hired 15 Black and Hispanic apprentices to learn filmmaking by working on the crew. One of them, Drake Walker, was responsible for writing the screenplay for Mr. Belafonte’s subsequent film, which was a gritty western titled “Buck and the Preacher” (1972) and starring Mr. Poitier as well.

But after appearing in the hit 1974 comedy “Uptown Saturday Night” with Mr. Poitier and Bill Cosby as a mob boss (a parody of Marlon Brando’s character in “The Godfather”), Mr. Harry Belafonte was once again absent from the big screen, this time until 1992 when he played himself in Robert Altman’s Hollywood satire “The Player.” Mr. Poitier directed both “Buck and the Preacher” and “Uptown Saturday Night.”

After that, he only made occasional appearances in cinema, the most notable of which was in the role of a mobster in Mr. Altman’s “Kansas City” (1996), for which Mr. Harry Belafonte won an award from the New York Film Critics Circle. In 2018, he appeared in the film “BlacKkKlansman” directed by Spike Lee, which was his final cinematic performance.

Participation in Politics

During the years that Mr. Harry Belafonte was not active in the entertainment industry, he continued to perform concerts, but his primary focus was on political action and philanthropic work. In the 1980s, he was instrumental in the organization of a cultural boycott of South Africa, as well as the Live Aid concert and the all-star recording of “We Are the World,” both of which generated money to combat starvation in Africa. In 1986, after receiving encouragement from a few prominent members of the Democratic Party in the state of New York, he toyed with the idea of running for the United States Senate. It was in 1987 when he took over for Danny Kaye as the goodwill ambassador for UNICEF.

He was never bashful in voicing his opinion, but during the presidency of George W. Bush, he became much more outspoken. In the year 2002, he accused Colin L. Powell, the Secretary of State, of betraying his convictions in order to “come into the house of the master.” Four years later, he referred to George W. Bush as “the greatest terrorist in the world.”

The mayoral election in New York City in 2013

Mr. Harry Belafonte was just as vociferous during the mayoral election in New York City in 2013, in which he campaigned for Democratic contender and eventual winner Bill de Blasio. He was a supporter of Mr. de Blasio. During the course of the campaign, he referred to the wealthy industrialist brothers Koch as “white supremacists” and linked them to the Ku Klux Klan. The Koch brothers are well-known for their support of conservative causes and their wealth. (Mr. de Blasio hastened to dissociate himself from those remarks).

Awards

Because of sentiments like these, Mr. Belafonte was frequently the subject of criticism, yet his artistic ability was never called into question. In his later years, he was awarded a number of prestigious honors, including a Kennedy Centre Honour in 1989, the National Medal of Arts in 1994, and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000.

The same year that his autobiography, titled “My Song,” was released, he was also the subject of the documentary film “Sing Your Song.”

In appreciation of his career advocating for civil rights and other issues, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences bestowed upon him the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 2014. This honor was presented to him in 2014. He told The Times that receiving the honor made him feel “a strong sense of reward.”

Harry Belafonte continued to be involved in political affairs right up until his death. On the day of the election in 2016, The Times published an opinion piece written by Mr. Belafonte. In the piece, he urged readers not to vote for Donald J. Trump, whom he described as “feckless and immature.”

“Mr. When speaking to African American voters, he wrote, “Trump asks us what we have to lose, and we must answer: Only the dream, only everything.”

Writer:

Francisca Oliveira