Summary:

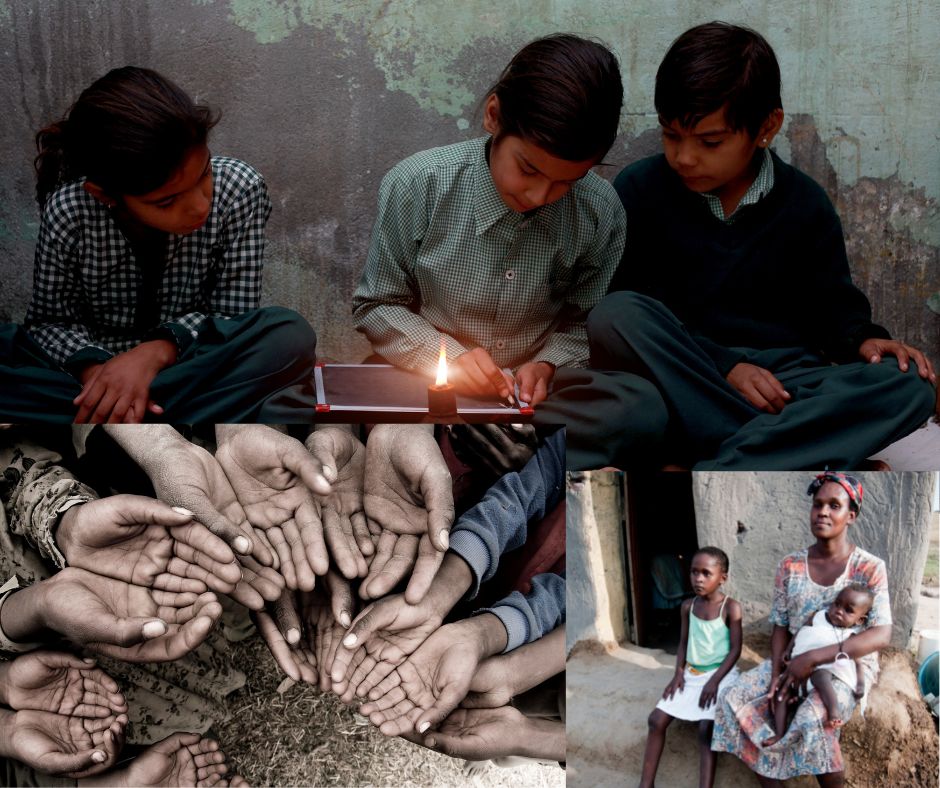

International Day of the Girl Child marks its tenth anniversary this year. Teenage females are most susceptible to environmental deterioration, natural disasters, and climatic stress. Climate change-affected families frequently have minimal resources, much less after a severe weather-related calamity. Girls and women have the most to lose from the adverse effects of climate change. Adolescent girls’ enrollment and retention rates in school dramatically decreased weather-related death, injury, and relocation at the community level.

This is because adolescent females’ self-confidence, leadership, communication, and life and livelihood abilities improved with each year of education or skill training. Climate-adaptive food systems can positively impact local suppliers, local food security, and the power of communities to weatherproof themselves. To accomplish this, we must ensure that everyone, especially women and girls, has access to the information and skills necessary to save lives and maintain livelihoods.

The International Day of the Girl Child marks its tenth anniversary this year. While the positive development needs of girls have received more attention in recent years, more has to be done before we can engage in and prioritize girl-centered solutions to the pressing global development concerns.

Teenage girls may play a critical role in developing climate-responsive solutions, which should not be undervalued given the triple planetary catastrophe of climate change, air pollution, and biodiversity underlined in UN Common Agenda discussions in August.

Teenage females are most susceptible to environmental deterioration, natural disasters, and climatic stress. Together with women, they make up an estimated 80% of people who a climate-related disaster has displaced and 60% of those who experience chronic hunger owing to food insecurity worldwide.

Recent UNFPA research has shown connections between household demands to survive climate change, limited and lost access to resources, and these stressors. Climate change-affected families frequently have minimal resources, much less after a severe weather-related calamity.

This pressure leads to early marriage or the trafficking of girls to provide a source of revenue and lower the household burden for those dependent on the environment for nutrition, health, and household resources.

Health and educational outcomes at the household, community, and national levels are adversely impacted by climate change when it exacerbates already existing inequities or the exclusion of girls, including their protection and access to the development of functional, soft, life, and technical skills; in some cases, this can last for generations.

What if, however, we could alter this negative dynamic? What if we could successfully tie adolescent girls’ resiliency, optimism, and resourcefulness to novel approaches to funding climate-related mitigation strategies?

What if we could use current environmental problems as a “tipping point” opportunity to improve how we approach and fund adolescent girls’ social and economic development?

Girls and women have the most to lose from the adverse effects of climate change. Still, they also stand to gain the most from methods for climate-friendly development that enable them to take an active role in and significantly contribute to community-led responses.

Suppose we comprehend adolescent girls’ current resources. In that case, the places they inhabit and the impact – apparent or otherwise – they have within families and communities can be the most potent catalysts for behavior and system change.

Adolescent girls’ enrollment and retention rates in school dramatically decreased weather-related death, injury, and relocation at the community level, according to an econometric study that spanned four decades from the 1960s to the early 2000s.

This is because adolescent females’ self-confidence, leadership, communication, and life and livelihood abilities improved with each year of education or skill training.

As these more educated and talented females reach adulthood, they have more influence over decisions and establish households that are inherently healthier, safer, and more successful.

There is a clear chance to make connections for people who occupy the land and are in the best position to safeguard its resources and the health and safety of their own families. Adolescent females will work in agriculture for the next generation, especially in rural areas.

Suppose education and skill development are prioritized for women, who make up 40% of the agricultural labor force globally and produce more than half of the world’s food. In that case, households will move beyond subsistence-level farming and become more involved as micro-businesses supporting farm-to-table supply and value chains.

This supports women’s leadership in diverse agricultural methods such as aquaculture and apiculture, as well as the link between these innovations and better health and nutritional outcomes.

To accomplish this, climate-adaptive food systems can positively impact local suppliers, local food security, and the ability of communities to weather-proof themselves by ensuring that everyone, especially women and girls, has access to the information and skills necessary to save lives and maintain livelihoods.

Even as we take immediate action to reduce the harmful effects of climate risk, we can take steps to tap into the power and resiliency of adolescent girls around the world.

First and foremost, we need to make more significant investments in secondary school, where girls drop out at the highest rates between lower and upper secondary levels. Building context-relevant climate-smart skills for the resilience of households and communities should be part of this investment.

As part of workforce development and intelligent financing strategies that include adolescent girls and young women, we must also support the establishment of environmentally friendly and climate-adaptive small businesses, particularly in rural areas where green jobs can improve rural-to-urban supply chains and overall food security.

Finally, to continue reducing mortality, injury, and displacement, we must design community development plans that consider how young people, particularly adolescent females, can support conservation and climate-risk reduction activities as part of civic engagement.

Without these progressive investments in adolescent girls as significant participants in community development, harmful social and cultural attitudes that prioritize a woman’s motherhood or marriage over her education and career (and discount her right to own land) will persist, perpetuating a pattern of enormously missed opportunities.