Summary:

-

Her Paris gallery, Air de Paris, revealed her passing after a brief illness.

-

She fought against censorship, followed her dreams, and went against social norms in her life and work.

-

Some of Iannone’s best-known—and most graphic—works were created in the 1970s, during her relationship with Roth.

-

Given its focus on sex, some people found her work obscene, while others thought it lacked enough feminist content (and heterosexual content).On and On with Dorothy Iannone (1979) Dottie IannoneOver the past 20 years, new curators and artists have learned about Iannone’s work and praised it.

-

The director of the Kunsthalle Bern insisted that the genitalia in her paintings be covered, so her work was not included in an upcoming show in 1969.

The American-born, Berlin-based artist Dorothy Iannone, who produced frank, pleasant, and outstanding art about pleasure and sexuality, has passed away. She was 89. Her Paris gallery, Air de Paris, revealed her passing after a brief illness.

The gallery said, “Love and freedom have been at the center of Dorothy Iannone’s work for six decades, with full power until her sudden death yesterday.” We will miss her a lot because she was a unique artist, a thoughtful and busy person, and a caring, fun, and kind friend.

During her long career, Iannone worked in many different ways. She used collage, video, sculpture, painting, sketching, and other art forms. Exploring female sexuality, desire, power, and emancipation was the central theme. She was skilled at fusing text and images. She became known for her colorful and graphic style, which she got from American comic books, Japanese woodcuts, Byzantine mosaics, Egyptian paintings, and Indian erotica.

Iannone thought there was a strong connection between the two, which is different from other female artists who don’t like it when their personal lives are used to explain their work. She fought against censorship, followed her dreams, and went against social norms in her life and work.

I Lift My Lamp Next to the Golden Door by Dorothy Iannone (2018) Timothy Schenck took the picture. Friends of the High Line, with permission

Iannone was born in Boston in 1933, and her mother reared her primarily after her father passed away when she was two. She studied English at Brandeis and Boston Universities but turned down a PhD fellowship at Stanford to marry James Upham, a wealthy investor and painter.

Iannone started taking pictures of famous people like Charlie Chaplin and Jacqueline Kennedy out of wooden cutouts when both became essential parts of the downtown New York art scene and traveled the world. Even when her cutout characters were fully dressed, their private parts were easy to see, which was a sign of her future interests. At the same time, she also made art in the popular Abstract Expressionist style.

In 1960, U.S. Customs took away Iannone’s copy of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer at a Queens airport. This made her famous. Later, with the help of the New York Civil Liberties Union, she sued the group and won. This forced the government to remove the ban on Miller’s work.

Seven years later, while traveling to Iceland, she met the artist Dieter Roth, which was a significant turning point in her life and career. She decided to leave her husband and move to Reykjavik within a week to be with him. He referred to her as his lioness, while she called him her inspiration.

They became famous as part of the Düsseldorf Fluxus movement, stayed together as lovers until 1974, and stayed close until he died in 1998. She moved to Berlin in 1976 on a scholarship and lived there until she died.

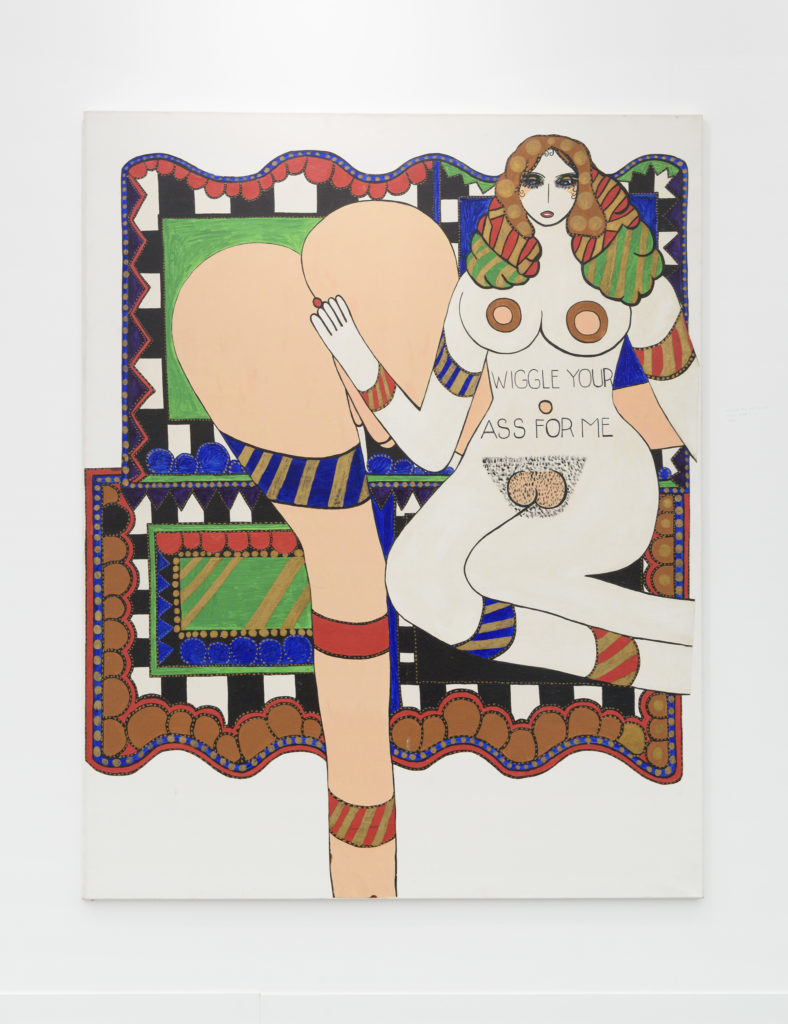

Please wiggle your ass for me, Dorothy Iannone (1970) with permission from Air de Paris, Paris

Please wiggle your ass for me, Dorothy Iannone (1970) with permission from Air de Paris, Paris

Some of Iannone’s best-known—and most graphic—works were created in the 1970s, during the course of her relationship with Roth. Both her and Roth’s flagrant delicto portraits had stars and flowers on them. Years before Tracey Emin made waves for doing the same, she constructed an artwork that listed every man she had ever slept with.

“The two of us became the main characters in my work,” she told Maurizio Cattelan in an interview for Flash Art. “Instead of using lines from poems I liked in my paintings, I now wrote down what we had talked about or wrote my own texts.” Now that I had found my own high love, I was no longer fixated on Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra. As I documented this love, not only did my art take on many new shapes and directions, but it also captured not only the ecstasy but also the home scene and its challenges.

Another important work in Iannone’s body is the video sculpture I Was Thinking of You III (1975). It is a human-scale box with a sensual scene painted on it and a built-in monitor with a video of the artist masturbating shown on the monitor. This piece made Iannone more well-known in the mid-2000s when it was remade for the Whitney Biennial in 2006 and the Wrong Gallery at Tate Modern in 2005.

“Even when no one else is there, I always feel humiliated when I see this movie,” the artist admitted in the Flash Art interview. “I don’t know how I did it, but I’m so glad I did,”

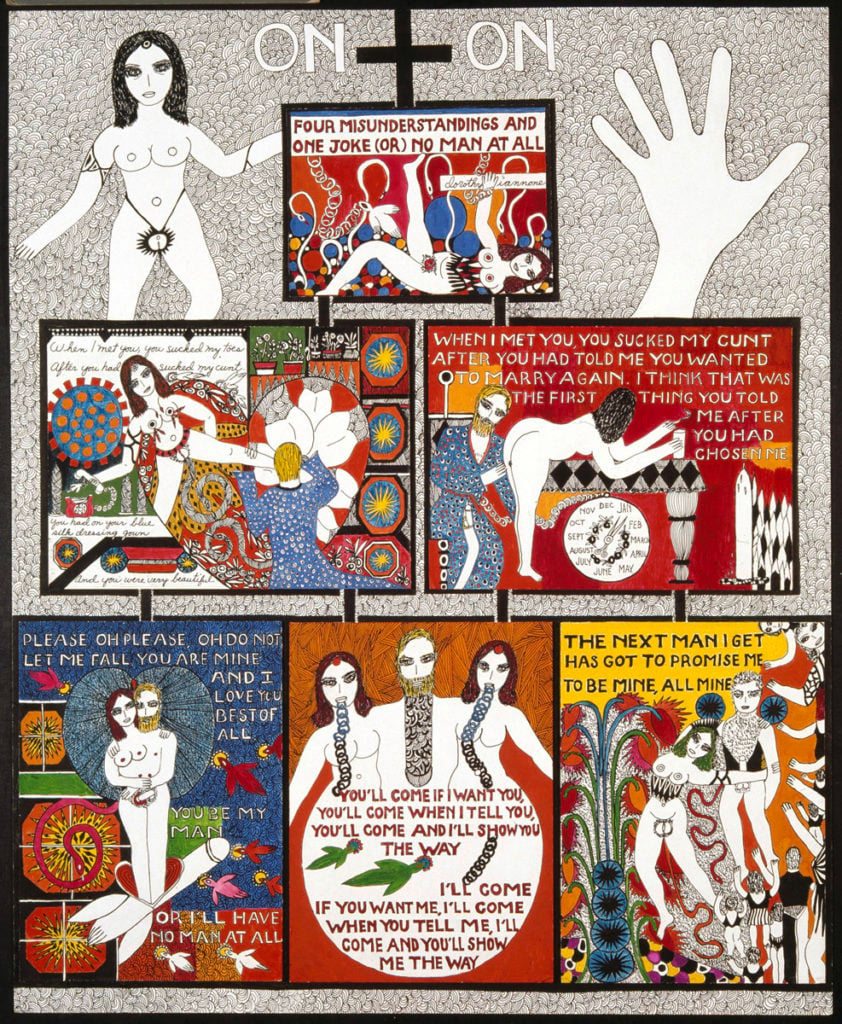

The art world was slow to catch up with Iannone. Given its focus on sex, some people found her work to be obscene, while others thought it lacked enough feminist content (and heterosexual content at that).

On and On with Dorothy Iannone (1979) Dottie Iannone

Over the past 20 years, new generations of curators and artists have learned about Iannone’s work and praised it. She was the focus of solo exhibitions at the New Museum in 2009, the Camden Arts Center in London in 2013, and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark earlier this year. Her work is in many collections, such as those at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, the Centre Pompidou, and the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in Paris.

Jan Voss, a friend and fellow artist, is said to have called Dorothy “the embodiment of all revolutionaries.” She made the decision about which hierarchy to respect and which to mock.

The director of the Kunsthalle Bern in Bern, Switzerland, said that the genitalia in her paintings had to be covered, so in 1969, her work was not in a show. (In response to Roth’s criticism, the curator, Harald Szeemann, resigned.) She wrote about what happened in a 1970 comic book called The Story of Bern (or Showing Colors). Iannone used everything as raw material, as usual.